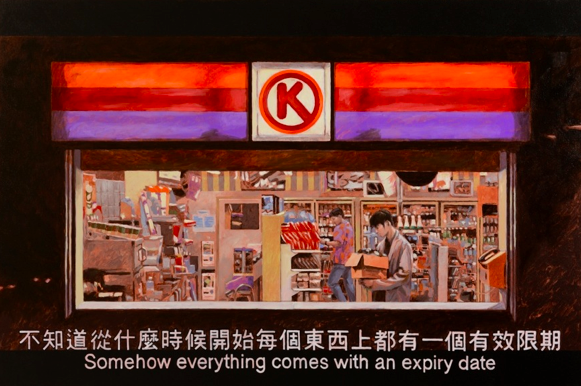

For several months over this past year I worked as an intern at the Klein Sun Gallery* in Chelsea. In my time there, I experienced several iterations of the gallery’s exhibitions. The Klein Sun Gallery’s representation is specific to contemporary Chinese artists, the majority of which have well established careers in China already. Themes intrinsic to Chinese sociology and national identity, as well as Chinese culture and history, are frequently addressed by the various artists who’ve shown work at Klein Sun. For example, traditional Chinese materials and crafting techniques are utilized by several artists, like Geng Xue, who works with porcelain or Gao Rong, who continues to incorporate the traditional practice of embroidery passed down in her family through the generations into her artwork. It is also common for artists to explore aspects of Chinese political history and contemporary society either explicitly or subliminally in their artwork. This is evident in artwork by Cai Dongdong, whose career as a photographer began during his time in the Chinese army during the Cultural Revolution. His photographs mock the forced formality of media from that period. Chow Chun Fai, whose solo show entitled Everything Comes With an Expiry Date, opened at the Klein Sun Gallery recently, also uses his his artwork to discuss politics and culture, producing paintings of subtitled film stills taken from famous movies about or located in Hong Kong. Chow picks the scenes he depicts with care. For example, the painting for which his show is named, Everything Comes with an Expiry Date, is a film still from the movie Chunking Express, and both the movie and the iconic line which Chow depicts are meant to reference the tensions which gripped Hong Kong before ‘the handover’ (or, ‘the return’ as it’s known in China) in 1977. All of Chow’s work does something similar, by directly referencing other forms of media which contemplate contemporary Hong Kong identity, the artist can express his own opinions on that identity with a multilayered, indirect approach. The issue with this practice is that it requires an intimate knowledge of Hong Kong’s political, social, and cinematic histories, knowledge which is more widespread in China and Hong Kong itself than it is here in America. Without the proper context, the significance behind the majority of Chow’s work is lost. This is a frequent issue at the Klein Sun Gallery. Some artists who are successful in China do not sell well in America, and I believe that this is because they don’t provide enough context about their work for it to resonate with an American audience. Especially when artwork is socially or politically charged, it is vital that the audience be able to recognize what makes it so, and if the message is too specific to one single culture, it will likely be misunderstood by outsiders.

*The Klein Sun Gallery is located at 525 West 22nd Street, New York